Last week, I downloaded Rosetta Stone and started to learn Greek. It’s something I have wanted to do since I was a little girl. I remember going to mass with my grandparents at the Greek Orthodox church. I would listen to my grandfather speak with his friends in impossibly long words that jumped and hopped across my eardrums. The men would laugh and grip each other on the shoulders. At the festival in the spring, the men would dance and shout. Some wore traditional dress. We would eat, eat. That’s how he said it. Always twice, as if I might hesitate without the extra encouragement.

He was whole in those moments. He shrugged off the restraint of fitting into a society that expected him to be buttoned up, English speaking, parsimonious of motion. He spoke in the language of his youth and exploded with the passion of his culture. And so, all those years ago, when I read the announcement for Greek school in the Sunday bulletin, I was surprised when he said a word to me that he rarely used, “No.”

I was crushed. I was too little to understand his experience. To me, learning Greek was another way to be closer to him. If I could speak his language, it would somehow tell him how much I loved him. Of course, he knew that already. But I was little, and he was my hero. My father tried to make me understand my grandfather’s position. He told me that my grandpa was grateful to have come to the United States and he felt it was somehow an insult to his adopted home to not speak English. I accepted it in the way children do, not understanding but trusting my father knew better than I.

Fifty years later, the weight of that moment hit me as I stood in a middle school cafeteria and watched students and their families sharing their cultures. Students, dressed in traditional clothing, danced with pride to a packed crowd. A father sat on a folding chair on the stage with his guitar and sang a folksong in Spanish. Food from every country was shared. Words spoken in languages coding shared-experience and common memories propelled people together, reuniting strangers who did not know they were long lost friends. The laughter and applause spoke volumes about this school. It is a place where students can come whole to their lives. It is a place where boys donned bright dashikis and girls ornate salwar to proudly represent their culture and family.

The educator in me has always known it is better for students and staff to bring their whole being to all the aspects of their lives. My heart has always known my grandfather could not. That buttoned up shirt, carefully spoken English, and contained movement were all denying a significant part of his being in hopes that he and his progeny would fit in. That breaks my heart. I cannot begin to appreciate his experience. I am not judging him. We all do what we have to do to survive. But my heart breaks that he could not bring the beauty of his culture and language to the rest of his life. He could not live fully whole.

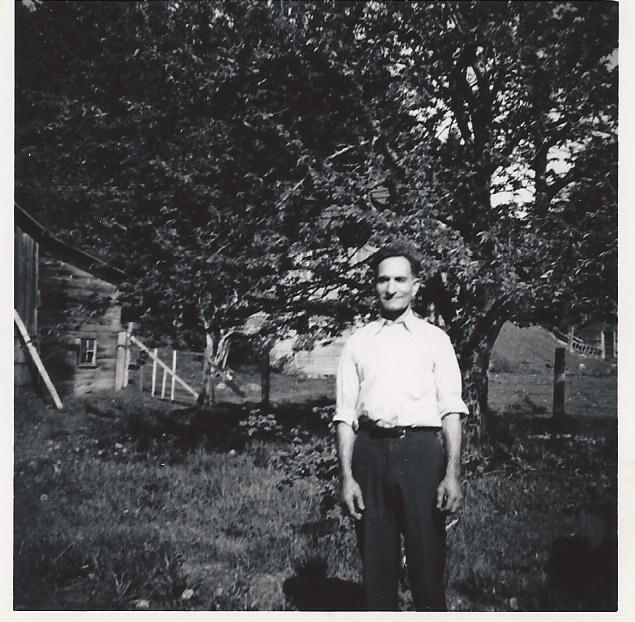

Dimitrios Paraskevoulakes was 18 years old when he stepped onto the S.S. Themistocles in Piraeus, Greece to come to the United States. The courage of that act overwhelms me even today. My eyes fill with tears every time I think of how lonely and frightening that must have been for a young man, though it is equally possible he was surrounded by friends and filled with the thrill of the voyage. Either way, that first step off the ship changed him forever. Outwardly. The truth is that even in his own home, he could not be wholly himself. He could not express himself in a language that would speak the words of his memory. The words whose meanings only someone who shared his lived experience would fully appreciate. Words chosen carefully for their subtle implication.

It has been my experience that the universe conspires to show us what we might know intellectually at the exact moment we are ready to understand it at the deepest level in our hearts as well. As I watched the sheer joy in that middle school cafetorium, the universe was teaching me that the world is a better place for everyone if we are allowed to bring our whole being to all of the parts of our lives. It doesn’t matter if we’re talking about our cultural, ethnic, racial, religious, gender diversity, sexual orientation, or familial elements of our being, it is always better when we can bring ourselves, our whole selves, to our lives and do it in a way that is open and honest.

Can you imagine what it must be like to go through the majority of your day unable to participate in a religious practice, eat familiar food that nourishes your body and soul, eschew traditional clothing or symbols, or speak in a language through which you can fully express yourself? Perhaps you know exactly what I am talking about.

At my age, given my career, professional experience, and education, I definitely knew all of this intellectually. But it took Rosetta stone, immigration documents from 1910, and a middle school multicultural night to push all that knowledge down until it reached my grandfather, who is always bubbling up in my heart, to really understand why it is so important for all of us to be able to show up and be welcomed whole into our lives. Though we are so much farther than we were when my grandfather stepped off the Themistocles, we have a long way to go as a society to get to the place where we can all bring our whole selves to our whole lives. We are making progress. I know principals and teachers who are creating that world in their schools today. I wish my grandfather could have been standing with me in that cafeteria. I could see him on stage dancing- not surrounded by other Greeks who shared the religious compartment of his life- but surrounded by people of many cultures who might share in his life. His whole life.

Leave a Reply to Gabi CoatsworthCancel reply